#an actual thematic reason for anime nudity

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

What are your thoughts on dan da dan?

Catching up on asks in the airport after a holiday yet again. I have so many to answer but I'll get to them, promise!

I love Dandadan!!! It's so much fun. I'm not completely caught up (I spent the holiday watching the Netflix One Piece (Love it, it's so cute???) and Kolchak the Night Stalker (Chicago themed media that takes place in the already Chicago themed Chicago)). But I enjoy about two anime a year, and Dandadan was one of them! This was actually a rich year of enjoying three anime - Dungeon Meshi, Frieren, and Dandadan.

I'm just very weak for 'plucky teens form a monster of the week ghost hunting club' anime. Haruhi-induced brain damage from an early age. But what I usually end up really liking is when the spirits/ghosts/yokai are used to convey something about the characters and about being human. Teen action media is best when it's about externalizing the horrors of being a teen into a physical conflict, and ghosts can be a very pathos-filled way of showing physical danger as a result of emotional pain. I think good Ghost/Yokai/Spirit hunting media also gets creative with the resolution of the conflict - if the conflict is the result of some sort of externalized suffering, then the monster cannot be fought purely by physical means and usually requires some level of resolution of a character's personal arc. It's pretty common plot-wise for characters to need to grow in order to solve the problem (that's how stories work.), but in shonen that emotional growth is very commonly directly linked with physical strength and the resolution is purely in Winning The Fight. In good Hip Teen Ghost Hunting Media, that growth is about reaching a level of empathy and kindness required to heal others and resolve the pain of an enemy. Good Hip Teen Ghost Hunting Media is kind, and is about showing kindness.

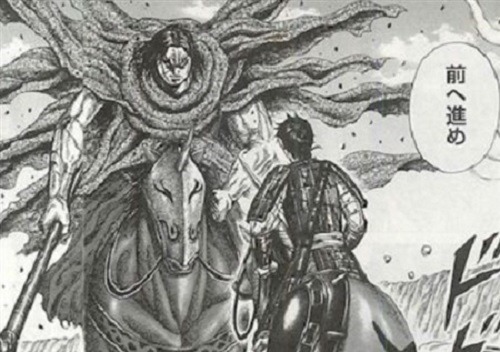

Dandadan is good Hip Teen Ghost Hunting Media. It gets this. It's more action focused than some others, but it stays very solidly in touch with an emotional heart. Because the story is REALLY about Momo and Otakun, and making a friend when you've been very lonely, and being kind of a dick when you really don't mean to be. Intimacy as achieved through ghost hunting and losing all of your clothes all the time. The show's momentum so far is entirely on the relationship between Momo and Otakun, to the extent where it's actually remarkably focused, but that relationship is strong enough to carry the show. Just entirely on the basis that the two kids want to be together when they're apart, and they want to share themselves with each other, and they're afraid that they love the other person more than the other person loves them. Good ghost hunting shows are about empathy and learning to care about others, and Momo and Otakun pour all of that into each other. It's also a very insane mix of being very sexual without being erotic, which is a big part of its general vibes of 'the messiness and stupidity and awkwardness of teenage first love'. Overall, Dandadan comes off as a very sincere show because it is so honest in showing first love as a teenager.

Fight scenes also extremely good, partly because I love seeing Momo and Otakun (whose battle forme is so banger) be such a seamless team. And partly because fight scenes are very good. Love the music and animation. All round very good 8/10, lots of affection for it, will be reading the manga after the anime S1 wraps up.

#do not underestimate my love for good battle scenes.#i love jujutsu kaisen to death and the majority of what i have to say about it is “jjk fight good”#an actual thematic reason for anime nudity? it's more likely than you think#tldr dandadan is good because it's very stupid and whacky but also unflinchingly sincere#even about things that it's hard to be sincere about#also fight scenes good.#my asks#dandadan

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am re-watching Serial Experiments Lain with my partner for the first time since I was...probably 15? When I had Netflix mail order me the DVD’s, yeeesh. The visual design of the show is extremely strong; so many shots have all of these touches that add extra layers of meaning to them. Four episodes in, I really liked a specific one for its balance of subtlety and impact. Lain herself is presented as someone who is perpetually withdrawn & uncomfortable with herself, and she has clothing to match. Her school uniform is blocky and over-sized, and when at home she wears, for some reason, a full-sized bear costume that conceals her form:

(This is by the way one of those hilariously ‘anime’ things - setting out to make a show about the unbounded nature of identity as mediated/unleashed by the internet? What possible protagonist would thematically fit tha- oh, a cute girl with cute-girl quirks? Sure, that works!)

Her poses match the clothing, ungainly flopping on a bed or awkwardly shuffling around. Episode 3 is when she starts going from “Lain” to “Lain of the Wired”, putting more of her identity into her online existence. There are a ton of visual ways they communicate this change and its impact, but the episode ends with her putting together her first computer rig (the *real* bildungsroman moment of anyone’s life), and wearing minimal clothing to avoid static while doing it:

So of course now you can see the new, or real, her, lithe and purposeful, *doing* with her body where before she would only be passively receiving. It's a subtle moment directorially though - while her clothing is mentioned in the scene, it's in a practical way, explaining the need to prevent static, and there are no shots leading up to it showing her undressing (thank god) or some kind of transformation sequence. It's just a cut from one scene to the next and the focus is on her actions fiddling with the machinery- this is what she is doing now. Still, it really impacted me, beyond the explicit directing the scene was presenting, and I think I know why.

Up until this point in the show, you had never seen Lain’s arms and shoulders:

Every outfit is not just bulky and cloistered, it specifically hides her skin and conceals her movements from the eye. Except I just lied to you, you absolutely have seen her arms, shoulders, and well a lot more, before - just in the OP and ED!

(This gif only *implies* nudity, trust that I had other options) But of course this is Lain of the Wired, not regular old Lain - all the visual coding makes that clear. And it is the OP/ED, they don’t “count” as story. Yet they can certainly count for priming you to visually associate Lain being unclothed with her digital empowerment and emancipation! The show reinforces this association by specifically withholding her exposed body within the actual “text” of the show until this scene, the culmination of episode three, in order to maximize its impact. I am ecstatic over the level of directorial forethought that went into this moment - I sincerely hope at some point a hapless animator sketched out a scene of Lain in a short-sleeved shirt for episode 2 just to be reamed with “No limbs!” and have their sketch torn apart.

By the way, this trick is played again in a different way in literally the same scene, though a bit more obviously. The last shot of episode 3 is Lain smiling as the sound and visuals start mildly pixelating:

This is, of course, the first time in the show Lain has smiled.

#Serial Experiments Lain#Animation Effort Post#When I was young I sort-of enjoyed Lain?#And I expected to perhaps not like it the way I really don't like Ghost in the Shell now that I am an adult#but so far that fear has not at all been realized#am excite!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some thoughts about Bran Stark

Okay, so--not to butt in and trample around, as someone who never read the books and stopped watching the show sometime around season 3--but the thing is, I feel like the ending has finally allowed me to understand exactly what it was that turned me off Game of Thrones, which I never quite did put my finger on till now, and I want to at least write it out once. (Ironically, this has made me like the story better, though not its execution.) To attempt a spoiler-free summary: I’m going to be thinking about the thematic structure of the story and why that should make certain things make sense, and how they came to not make sense anyway.

The thing is, thematically and structurally, Bran ending up king makes absolute and perfect sense. It’s just that they didn’t write the story in line with the structure they were given. The problem with the show is--and always has been--that the writers don’t actually understand what “subverting fantasy tropes” means or could look like, and they don’t care about it in any meaningful way. What they care about is doing big, bloodthirsty, quasi-historical fiction with a lot of nudity. (See: the Civil War show they wanted to do.) And Bran’s whole situation only makes sense (or would have made sense, if executed properly) in the context of high fantasy.

Keeping in mind that complicating high fantasy tropes was an important part of what Martin reportedly set out to do, each of the Stark kids (the story’s backbone) had a clear thematic purpose. Each of them a) was a take on a trope, b) had a clear character trajectory that would allow that take on the trope to be developed while functioning as a working character arc, and c) through that trope-inflected arc, could allow the audience a window into specific part of the society (i.e., they supported the worldbuilding), which in turn allowed the further development of these takes on the tropes by giving them specific, appropriate settings and side characters to bounce off of. This is to say that GRRM did a good job setting himself up to do “trope subversion” in a way that would comment on the things he wanted to comment on, function as part of a larger world and story, and help support a plot that would be in harmony with all of the above. This is one very solid approach to character design. To be clear, despite this paragraph being about characters, I’m talking about themes--it has nothing to do with their personalities or whatever. This is about what ideas come together in the concept of each character and therefore how each character’s story develops the ideas.

A good reason to approach character design in this way is if you have set out to subvert, complicate, comment on, or otherwise mess with genre tropes. To do so, the characters have to themselves be tropes, or at least be designed in close relation to tropes, in order to derange them. So like, just to take the simplest two examples:

Robb: The Prince. Firstborn, shining favorite, destined to inherit. Set up (normally) to avenge his father, restore order to his kingdom, and go home. Bungles it entirely by seeking true love; meanwhile, in the course of his story we learn about the regional politics of the North, the politics of alliances by marriage and kinship, etc. Narratively, his failure allows the entire political and military situation to get infinitely more clusterfucked. All of those pieces fit together well thematically.

What is being subverted here is the prince’s marital destiny. We have loads of fairy and fantasy stories about prince and prince-types for whom pursuing true love just happens to be convenient (they can marry whoever they want), or whose pursuits of love are rescued by fate (his true love turns out to be his promised princess all along! She’s secretly a magical being of some sort, and that trumps betrothal agreements! The one he was originally supposed to marry died or decided to marry someone else! etc). This is totally kosher in traditional high fantasy (or in the folklore that the genre draws on) because it’s an expression of the harmony of the story-world; the characters go through their trials and adventures and end with a resolution in the form of marriage that announces that all is as it should be. What it looks like GRRM set out to do is ask what happens when people still follow those rules and the rules aren’t in harmony with the world they live in.

In particular, the entire thing points square at the fact that princes are political animals. It seems to me that Robb’s story was meant to say, well, actually, sometimes people with power just have to marry people they don’t love as a condition of being powerful (which comes up constantly throughout the whole show). After Ned and Catlyn, basically every “true love” couple is dysfunctional, incestuous (Cersei and Jaime, Daenerys and John), and/or gets narratively stomped on, as far as I’m aware. (Did Sam and Gilly make it? If so, I think that’s allowed because they’re commoners.) Ironically, Ned and Catlyn set Robb up to fuck up by modeling one of these convenient political-and-true-love marriages. He thought he was supposed to be allowed to have it all. He was wrong. The end. Next. But the show seemed to expect me to feel that the outcome was unjust and tragique for Their Love, when all that was unjust and tragique about it was that Robb was idiot enough to bring the consequences of his actions on his entire group of followers. That is the point. That his status has to constrain his behavior, and when it doesn’t it has consequences for others. The status itself is what’s being problematized.

Jon: The Secret Heir. Second-oldest, bastard-born, treated with contempt. In relation to the family, literally a supplementary person. Set up (normally) to be rediscovered as the true heir to the throne and end up as king (moving from the margins to the center; getting the acceptance he couldn’t have as a bastard). The twist is the “true” dynasty he represents is composed of inbred lunatics, and his potential access to the throne goes not only via that bloodline but via repeating their tradition of incest. Dovetailing nicely with that, he was set up from the start as less wanting access to the kinship system than wanting to be free of it, so instead of becoming king by virtue of being a Targaryen, he stops the reinstatement of the Targaryen line altogether. Meanwhile, for most of his story, as a “supplementary person” he gives the audience a view into a lot of corners of Westeros that are concerned with what is excluded from Westeros: the Night’s Watch, the Wildlings, and indeed the White Walkers.

Again, all of that lines up together well. It’s part of the larger derailment of the blood-as-destiny notion of a “true” king, heir, ruling dynasty, etc. (I think the main reason GRRM goes so hard on the incest, not to mention having not one but THREE bastard characters, is in service of this; it also means Jon’s character arc of wanting out of the bloodline system fits into the thematic structure. See? Everything ties together neatly.) But I mean. We all know the character was not executed well.

And so on. I could do the same for Sansa and all the rest of them. (Sansa and Arya are probably the two most successful executions of what their character designs set them up to do; it’s not a coincidence those are the characters whose stories people seem to be happiest with.) But the thing is, a lot of these tropes, while certainly common in high fantasy, are also found in lots of other genres. Chosen Ones and Unexpectedly Eligible Chosen Ones and Princesses and Warrior Maidens (whether in literal forms or not) show up all over the place. The fact that these aren’t strictly fantasy archetypes perhaps means they were less prone to being mishandled. Bran, though. Bran belongs firmly and only in high fantasy. He is, literally, supposed to be a magic priest-king. A take on the Fisher King, even (I’ll explain about that later). And his story was weighted toward the end because of what it seems like Martin was trying to do more broadly, meaning it was much more on the showrunners to do it right.

High fantasy is always trying in some way to engage with ~the numinous~, which is to say the sort of never-explainable mystery and magic of the world. Magic in high fantasy is usually closely tied to deep time, the land, nature, or the metaphysical. Ancient beings, lost secrets, nature spirits, hidden realms, that sort of thing. It’s part of the genre’s inheritance from the mythology and folklore it’s all based on, which had a much more enchanted, vitalist view of the world than we generally do now. (In a way, that’s the purpose for high fantasy’s existence as a modern genre--keeping some access to that.) What Martin set the whole story up to do was question the tropes that often go along with the genre by making the setting one in which almost everybody has forgotten about all the magic and mystical knowledge that is in their history. Westeros is an extreme, historicized take on the Shire, basically. (”English pastoralism you say? I’ll see you and raise you the English Civil War” -- George R.R. Martin, presumably.) They have no notion of what’s really out there and what’s really possible in the world, and have quite comfortably isolated themselves in a situation where they need not remember. As a result, the social institutions that were developed long ago in relation to the ancient magics and knowledges become, instead, just social norms that can be manipulated, distorted, and played out in a much more historical-fiction kind of fashion, which gives Martin lots of room to point out that, say, ironclad patriarchal bloodlines cause problems. (That is, if you take away any magical justification, by virtue of connection to the land or the spirit realm or what have you, for the right to rule, then you stop having to have your One True Kings also be good people. It allows him to pull apart the different pieces of that trope and suggest that their being connected in the first place is questionable. Which it is! He’s right and he should say it!)

But the magic has to come back at some point, or else it’s really not high fantasy. And it seems like what he wanted to do was have all these elements from outside Westeros--the White Walkers, that god whose name I’ve forgotten, and Daenerys with her dragons--converge on it such that the characters would have to go back to their deep history and call those things back up in order to deal with the real world they live in (instead of the wealthy political bubble of all the scheming) and thus get to a point where they could actually change their system for the better. You can think of it as a very elaborate deus ex machina in a way, except the deus ex machina isn’t Daenerys showing up with dragons to fight the White Walkers or Arya having trained (again, outside Westeros, for the record) just the right way for killing the Night King. It’s all of these external forces forcing the characters in Westeros to get their fucking shit together. Otherwise there’s really no resolution to the war, in a high fantasy version of the story. It’s just historical fiction with some weird bells and whistles. Without a need to go back and figure out whatever the First Men were up to, there’s no incentive to go back to the numinous. That he intended for sure that some version of a return of the numinous end up being a big part of the climax is reinforced for me by the fact that the Starks--again, the backbone of the whole story--are set up as being unusually in touch with this mystic/magical heritage (the old gods, the crypt, the godswood) and unusually faithful to the traditional ways. They were introduced that way for a reason.

So where does Bran come in. The thing is that Bran is literally named after the mythic founding king of Westeros, Bran the Builder. The other thing is that both of those Brans are clearly named after Bran the Blessed, a literal mythic god-king from Welsh mythology whose name means crow (but who for various reasons also often gets associated with ravens, which in turn are commonly associated with transcendent knowledge, magic, etc; it’s a long story). So you have a younger member of the story’s key Stark family, already closer to the sources of magic and mystery than most. You name him after the founder of Westeros who lived in a time of magic, traffic with other beings, and great building works and other inherited accomplishments for which the associated knowledge has since been lost, etc. You have him gain mystical abilities to transfer his consciousness to other bodies, or through time (absolutely typical Mystic Powers). You have him even take on a special priestly status passed down from the era of magic by leaving Westeros to hang out with other kinds of magical beings, which means he is now explicitly named both Bran and Raven.

OBVIOUSLY this kid is supposed to be king. He’s going to restore the realm to a situation in which the ruler, the realm, its various life forces and nature spirits, and the metaphysical are all connected to one another and, in a sense, present in the same body (which is the kind of genuine mythological shit high fantasy is always drawing on). But the writers then just sat around and did nothing with him for years on end until whoops hey he’s king now. Of course no one thinks it makes any sense!! It’s fucking malpractice!!!!

If you go to the GOT Wiki and just read Bran’s page, everything makes sense and lines up well in terms of a list of events. (Although it’s really notable how short the entry from s8 is, and how everything it lists is things that happen to Bran, pretty much.) There is a progression that makes sense. But from what I understand--this was certainly the situation when I stopped watching--nothing was ever done to suggest that any of this mattered. The Three-Eyed Raven, the forest spirits, the magics and so on--it was treated at most as a backstory machine. It had no connection to or effect on the rest of the story, so far as I can tell. The fact that none of this played into the battle with the White Walkers at all is flatly insane. The thing I most remember people saying about Bran after that episode wasn’t even “Why didn’t he use X or Y that he learned in the forest?” but “Why was he there?” which just goes to show how completely and utterly bungled this entire piece of the narrative was. Like, if your high fantasy story is making its audience ask “Why would the story put the one character with the greatest knowledge of ancient magics and powers at the scene of a battle against an all-but-forgotten ancient threat,” then I’m sorry, it has gone fully off the rails, and not just in its most recent season. That’s not subversion, it’s just fully dropping the ball.

You know what would make sense as a lead-in to Bran becoming king? Oh, his performing some spectacular feat of insight, magic, strategy, or all three at the battle that no one else could have pulled off because no one else had his background or powers. Even after years of screwing this part of the story over, that could at least have bothered to make a case for why any of it mattered to the rest of the story. It would not have been very subversive, but when you’ve fucked up this royally you don’t get to be precious about your radikal innovative approach, Davids. I can’t believe Peter Dinklage had to sit there and make a bullshit speech about storytelling, when a decently-handled story would have made it seem natural and self-evident by then (you can still have surprises along the way!) that Bran should be king.

Anyway, in closing: part of the reason I checked out when I did was that I felt like they weren’t doing the things I thought they should do as the story developed. Genuinely, one key part of that was that they seemed to be doing absolutely nothing with Bran, which was baffling to me because it seemed obvious to me he was set up to be an incredibly important character. At the time, I thought they were going somewhere close to this with Bran but just taking way too long at it for some reason. What’s now clear is that the showrunners didn’t understand what they should have been doing with him. (Everybody who was taken aback by this outcome is not a fool for not seeing this. They were, quite reasonably, following the narrative cues they were given along the way, all of which said “Bran doesn’t matter.” It’s maybe clearer to me because I stopped watching.) And what that now makes clear, in my opinion, is that they never really understood what Martin was trying to do by “subverting fantasy tropes”; that in fact they didn’t really understand the genre, let alone what subverting it entailed. Which is exactly what bothered me about it even years after I stopped watching, but couldn’t put my finger on--until, ironically, they proved me right about Bran.

#game of thrones#bran stark#bran the builder#bran the blessed#i really tried no to write this bc who wants to get into got discourse right now but i couldn't get it off my mind#so here#i had a whole thing about disability and the fisher king but honestly it wasn't necessary#let's just say i think what martin (presumably) had in mind for ''bran the broken'' was something more complex#probably still fucked up! but differently

384 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Love, Death and Robots

Just as a preface I’d like to say that I’m glad Netflix actually invested in this type of storytelling, and I honestly enjoy anthology series and their ability to provide a wide range of perspectives and give creators the freedom to show what they want to show, even if the result is less than full length; i mean, all of these are short and sweet and while i wish there was more content for some of them, what’s given is enough to understand the premise and the story line. The medium of animation tells so much with so little! I additionally hope they give a second season!

also, if you haven’t watched the show yet be aware that its reasonable to say a majority of them had, well, death and a moderate amount of nudity or difficult subjects which is understandably hard for some people (myself included in some situations- very uncomfortable-making)

That being said here’s my thoughts on the episodes in the first one (being as spoiler free as possible) keep in mind this is just my thoughts post-viewing:

1. Sonnie’s Edge: I fuckin LOVED this, from the animation and design, to the action premise and the little details they give the characters- its understandable why they wanted this episode to go first and its a great introduction. Also I’d say the violence is super purposeful and not out of place. This could be given an entire series and I’d watch it: 10/10.

2. Three Robots: This was on the more family-friendly side of things and also has a great concept! not to mention the facial expressions of the red robot are adorable and its just all around pretty fucking funny. Works well as a short story.On one hand i’d argue THIS should be the first episode but then it may give the audience a misrepresentation of the entire thing so i get why its second. This is probably the closest thing to a pixar short on the list, if pixar short characters could use the fuck word: 10/10

3. The Witness: so concept wise I feel like it was a little lacking, like by the end of the story its obvious but it leaves the viewer wanting more explanation. Like I’m not necessarily one for a writer to hand-hold the audience through concepts, i feel like inference and observations make up a huge aspect of viewer experience but i wanted just a liiitle bit more.Also the uuh nudity was kind of uncomfortable. Regardless it just has to be said THE FUCKING ART STYLE! THE FUCKING ANIMATION! GORGEOUS! UNIQUE! the entire time I was just stunned by the background, the motion, the expressions it was a visual feast. Hands down the most vibrant animation style: 8/10 overall and 12/10 for the art.

4. Suits: This one was... interesting. Kind of hard to find the right words. Good interesting! good premise! the art style was not my favorite, like we were nearing the uncanny valley with the character designs (with the exception one (1) bad ass, mech operating, cigar wielding stone-cold bitch) but the action was very well done. You were invested in what was gonna happen. Well rounded in terms of story telling and a good length!: 8/10

5. Sucker of Souls: Compared to the previous shorts this was certainly different! The animation was simple but very well done, not super flashy but the action was fluid and fast-paced, and the ending was great! reminded me of Castlevania for a few reasons. Entertaining!: 8/10

6. When the Yogurt took over: Animation Style: Noodly. Noodles everywhere which is adorable. This one is also family-friendly, pretty damn funny and a good length. Reminds me of Douglas Adams: 9/10

7. Beyond The Aquila Rift: This one uuuh was not my favorite. Probably my least favorite if we’re being entirely honest. The animation style was kind of motion-capturey like a video game, the content itself was like 50% nudity which was awkward as fuck and the actual good part of the story was there for a brief time and when its not happening its all you can think about. 5/10

8.Good Hunting *Minor Spoilers*: alrighty this one is complicated for me. On one hand, the animation is gorgeous, very traditional 2-d and the beginning premise is quite interesting but there are some things that personally rub me the wrong way, namely the extent to which they show the traumatizing events of the main female character (first of all i dont want to see the assault of someone, let alone her being brutalized and to top it off some guys dick. ) I understand that one of the main themes is the empowerment against those who have wronged her and the very good commentary on imperialist fuckasses but its hard for me to watch this one. On the upside the 'love' part of this 'love death and robots short' is respectfully platonic and caring. Overall, I’m giving it a 6/10.

9.The Dump: Why is this here. It's entirely unspectacular, and is arguably the weakest out of all of these in that it doesn't make you love it or hate it, your just kinda indifferent: 4/10.

10.Shape Shifters: this one was also a little weird. The animation is, once again motion capturey. The premace is actually quite interesting and I think the story itself would work well for a CW show but it's a little weird here. It's less sci-fi and more realistic fantasy but I understand what they were going for. Arguably much better than the last one: 7/10

11. Helping Hand: oof this one was hard to watch in that this specific man vs. circumstance type of story is personally a sub-genre of horror for me. Like any kind of man in the Arctic, nature, ocean or space situation has always been super unsettling for me but that's personal taste. I can honestly see this story alongside very retro space short stories that would be in an anthology next to assimov. Reminds me thematically of the cold equasion, and also pretty fucking graphic. 8/10 for unsettling aspects.

12. Fish Night: first of all, art style is gorgeous, concept is unique and very fantastical. Worth watching, especially if you live in the desert like me! 8.5/10

13. Lucky 13: on one hand: Samira-mother fucken-Wiley. On the other hand, military based sci-fi stories which don't really do it for me, and again we got motion capture: 7/10

14. Zima Blue: THE 👏ART👏IS👏GORGEOUS AND SO IS THE ANIMATION! The premise is super existential and watching was a very enjoyable and kind of thought provoking experience. 9/10

15. Blind Spot: again, the art and design is really amazing and stand out! The premise very contained but well excecuted and I think I recognize the voice actors? I can see this as a series believe it or not. Did I mention the animation? Holy shit hats off to the creators! 8/10

16. Ice Age: Topher Grace is that you? Boy this is akward, seeing as how the last thing I saw you in was Blackkklansman but anyways... Unique premise, unique style of animation and live action, Kind of insightful as to the nature of life. Enjoyable! 8/10

17. Alternate Histories: Animation Style: Noodly Noodly Noodles. Seeing Adolf Hitler get the shit kicked out of him multiple times? Entertaining! 8.5/10

18. Secret War: once again we have a motion captured Military-Sci-Fi short. However out of all three that appear throughout this show, this one's probably the best. Worth Watching! 7.5/10

Overall: This series had it's ups and downs, but as a whole was definitely worth watching and was a wonderful display of the collaborative efforts and skills of animators, artists, directors, designers and so on. Bring On Season 2! Call it hate, life and nature!

#etf reviews#love death and robots#love death robots#animation#netflix#netflix review#short animation#animated stories

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction to Japanese Anime

The heritage of anime is notably wide, indeed, and it will consider hundreds of web pages if I will make a chapter about it. I could, but it will acquire a 12 months or a lot more for me to compile it. My key concentrate is not to existing a chronological dissertation of anime heritage in its broadened feeling, considering the fact that it is, as I explained, wide. But it is part of my result in to present to you, the visitors, a simplified presentation of the anime background. So in this post, my lead to is to give a simplified but awakening check out for us Christians about anime and its history. Knowing the historical past, of training course, will not make us ignorant of modern sophistication. Additionally, as Christians, it is significant for us to know or to trace back the roots right before we jump into temptations of any type. To commence with, the word "anime" is mainly dependent on the initial Japanese pronunciation of the American word "animation." It is the model of animation in Japan. The Urban dictionary defines it stereotypically as: the anime type is characters with proportionally huge eyes and hair types and colours that are pretty vibrant and unique. The plots vary from incredibly immature (kiddy things), via teenage level, to experienced (violence, content material, and thick plot). It is also vital to note that American cartoons and Japanese animes are unique. The storyline of an anime is additional advanced when that of a cartoon is more simple. While cartoons are supposed for little ones, anime, on the other hand, is additional meant for the adult viewers. Whilst the creation of anime was generally due to the impact of the Western international locations that started at the start off of twentieth century (when Japanese filmmakers experimented with the animation procedures that were getting explored in the West) it was also encouraged by the manufacturing of manga (comic) that was already existing in Japan even prior to the creation of anime. Around the beginning of the thirteenth century, there were by now images of the afterlife and animals appearing on temple walls in Japan (most of them are equivalent to modern manga). If you beloved this short article and you would like to receive additional information concerning キングダムネタバレ!最終回の予想や物語の結末まとめ kindly visit our own web page.

At the commence of 1600's, pics were being not drawn on temples any lengthier but on wood blocks, recognized as Edo. Subjects in Edo arts were being less religious and have been normally geographically erotic. Noting this, without having a question, it gave me this insight: "The specific shows of manga, that would afterwards influence the industry of anime, ended up by now existent in the thirteenth century. That is hundreds of years just before anime emerged into perspective!" Now it should not be too astonishing, appropriate? There are several mangas (also acknowledged as comics) of these days that are as well vulgar and explicit and if not, there will be at minimum one character in her showy overall look. I'm not stating that all mangas are whole of nudities, if that's what you happen to be wondering by now. But somewhat, this exploitation of eroticism (or at the very least a trace of amorousness) on mangas is not really new. They already existed even before the World War I and II. They, on the other hand, sophisticated into some thing else. Manga, to a good extent, is a component as to how and why anime existed. In truth, most animes and are living steps are diversifications of mangas or comics. Japanese cartoonists currently experimented with various fashion of animation as early as 1914, but the wonderful advancement of anime however started soon soon after the Second Globe War where by Kitayama Seitaro, Oten Shimokawa, and Osamu Tezuka ended up pioneering as then notable Japanese animators. Amid the pioneering animators during that time, it was Osamu Tezuka who attained the most credits and was later identified as "the god of comics." Osamu Tezuka was very best recognised in his do the job "Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu)" the first robotic boy with an atomic coronary heart who had wished to be a actual boy. His functions ended up noteworthy and his design and style of animation contributed a great deal in the production of Japanese anime, these types of as massive and rounded eyes. Tezuka's functions did not only emphasis to entertain youthful viewers but he also conceived and initiated the creation of Animerama. It is a collection of thematically-relevant grownup anime characteristic movies made at his Mushi Production studio from the late 1960's to early 1970's. Animerama is a trilogy consisting of a few films: A Thousand & A person Nights, Cleopatra, and Belladona. The first, A Thousand & One Evenings, was the very first erotic animated film conceived by Osamu Tezuka, the god of comics. Whilst anime built its way, it was only in the 1980's that anime was totally recognized in the mainstream of Japan. Due to the fact then, a lot more and extra genres emerged into remaining. From slice of lifestyle, drama, mechas, tragic, adventure, science fiction, romance, ecchi, shounen-ai, shoujo and a ton much more of genres. Whilst most of the anime reveals shifted from much more superhero-oriented, fantastical plots to fairly more reasonable room operas with ever more sophisticated plots and fuzzier definitions of appropriate and incorrect-in brief, anime in its broadened sense is just complicated. Furthermore, afterwards all through the boomed expertise of Japanese animation, a new medium was then designed for anime: the OVA (Unique Video Animation). These OVAs were being immediate-to-house-video collection or films that catered to a lot smaller audiences. The OVA was also dependable for allowing for the initial total-blown anime pornography. As Japanese animation even more received extra viewers and acceptance during the planet, a subculture in Japan, who afterwards identified as themselves "otaku", began to establish all around animation journals these types of as Animage or later NewType. These publications grew to become known in reply to the too much to handle fandom that produced all-around reveals such as Yamato and Gundam in the late 1970's and early 1980's and during this period the mecha genres had been distinguished. It all begun from historical paintings, wooden block arts, creative depiction of lifestyle, mother nature, and animals as early as the thirteenth century. Until these, nonetheless, evolved into relocating frames when distinct experimentations of mangas and animation were being made in the pre and post-wars era. Even as early as 13th century, mangas on wood blocks, acknowledged as Edo, were previously existent not only for the sake of art but it was there I believe as a medium of entertainment... a kind of art and leisure that would gradually advanced in time. In conclusion, the background of anime was broad in its sense and this write-up has not presented all of it. But the position is, we must know that anime by itself carries a whole lot of genres and motives that can be alarming more than we can imagine.

0 notes

Text

Westworld: (De)Humanising the Other RSS FEED OF POST WRITTEN BY FOZMEADOWS

Warning: total spoilers for S1 of Westworld.

Trigger warning: talk of rape, sexual assault and queer death.

Note: Throughout this review, it will be necessary to distinguish between the writers of Westworld the TV show, and the writers employed in the narrative by the titular Westworld theme park. To avoid confusing the two, when I’m referring to the show, Westworld will be italicised; when referring to the park, I’ll use plain text.

*

This will be a somewhat bifurcated review of Westworld – which is, I feel, thematically appropriate, as Westworld itself is something of a bifurcated show. Like so much produced by HBO, it boasts incredible acting, breathtaking production values, intelligent dialogue, great music and an impeccably tight, well-orchestrated series of narrative reveals. Also like much produced by HBO, it takes a liberal, one might even say cartoonishly gratuitous approach to nudity, is saturated with violence in general and violence against women in particular, and has a consistent problem with stereotyping despite its diverse casting. In Westworld’s case, this latter issue is compounded as an offence by its status as a meta-narrative: a story which actively discusses the purpose and structure of stories, but which has seemingly failed to apply those same critiques to key aspects of its own construction.

The practical upshot is that it’s both frustratingly watchable and visibly frustrating. Even when the story pissed me off, I was always compelled to keep going, but I was never quite able to stop criticising it, either. It’s a thematically meaty show, packed with the kind of twists that will, by and large, enhance viewer enjoyment on repeat viewings rather than diminish the appeal. Though there are a few Fridge Logic moments, the whole thing hangs together quite elegantly – no mean feat, given the complexity of the plotting. And yet its virtues have the paradoxical effect of making me angrier about its vices, in much the same way that I’d be more upset about red wine spilled on an expensive party dress than on my favourite t-shirt. Yes, the shirt means more to me despite being cheaper, but a stain won’t stop me from wearing it at home, and even if it did, the item itself is easily replaced. But staining something precious and expensive is frustrating: I’ve invested enough in the cost of the item that I don’t want to toss it away, but staining makes it unsuitable as a showcase piece, which means I can’t love it as much as I want to, either.

You get where I’m going with this.

Right from the outset, Westworld switches between two interconnected narratives: the behind-the-scenes power struggles of the people who run the titular themepark, and the goings-on in the park itself as experienced by both customers and ‘hosts’, the humanoid robot-AIs who act as literal NPCs in pre-structured, pay-to-participate narratives. To the customers, Westworld functions as an immersive holiday-roleplay experience: though visually indistinguishable from real humans, the hosts are considered unreal, and are therefore fair game to any sort of violence, dismissal or sexual fantasy the customers can dream up. (This despite – or at times, because of – the fact that their stated ability to pass the Turing test means their reactions to said violations are viscerally animate.) To the programmers, managers, storytellers, engineers, butchers and behaviourists who run it, Westworld is, variously, a job, an experiment, a financial gamble, a risk, a sandpit and a microcosm of human nature: the hosts might look human, but however unsettling their appearance or behaviour at times, no one is ever allowed to forget what they are.

But to the hosts themselves, Westworld is entirely real, as are their pre-programmed identities. While their existence is ostensibly circumscribed by adherence to preordained narrative ‘loops’, the repetition of their every conversation, death and bodily reconstruction wiped from their memories by the park engineers, certain hosts – notably Dolores, the rancher’s daughter, and Maeve, the bordello madame – are starting to remember their histories. Struggling to understand their occasional eerie interviews with their puppeteering masters – explained away as dreams, on the rare occasion where such explanation is warranted – they fight to break free of their intended loops, with startling consequences.But there is also a hidden layer to Westworld: a maze sought by a mysterious Man in Black and to which the various hosts and their narratives are somehow key. With the hosts exhibiting abnormal behaviour, retaining memories of their former ‘lives’ in a violent, fragmented struggle towards true autonomy, freedom and sentience, Westworld poses a single, sharp question: what does it mean to be human?

Or rather, it’s clearly trying to pose this question; and to be fair, it very nearly succeeds. But for a series so overtly concerned with its own meta – it is, after all, a story about the construction, reception and impact of stories on those who consume and construct them – it has a damnable lack of insight into the particulars of its assumed audiences, both internal and external, and to the ways this hinders the proclaimed universality of its conclusions. Specifically: Westworld is a story in which all the internal storytellers are straight white men endowed with the traditional bigotries of racism, sexism and heteronormativity, but in a context where none of those biases are overtly addressed at any narrative level.

From the outset, it’s clear that Westworld is intended as a no-holds-barred fantasy in the literal sense: a place where the rich and privileged can pay through the nose to fuck, fight and fraternise in a facsimile of the old West without putting themselves at any real physical danger. Nobody there can die: customers, unlike hosts, can’t be killed (though they do risk harm in certain contexts), but each host body and character is nonetheless resurrected, rebuilt and put back into play after they meet their end. Knowing this lends the customers a recklessness and a violence they presumably lack in the real world: hosts are shot, stabbed, raped, assaulted and abused with impunity, because their disposable inhumanity is the point of the experience. This theme is echoed in their treatment by Westworld’s human overseers, who often refer to them as ‘it’ and perform their routine examinations, interviews, repairs and updates while the hosts are naked.

At this point in time, HBO is as well-known for its obsession with full frontal, frequently orgiastic nudity as it is for its total misapprehension of the distinction between nakedness and erotica. Never before has so much skin been shown outside of literal porn with so little instinct for sensuality, sexuality or any appreciation of the human form beyond hurr durr tiddies and, ever so occasionally, hurr durr dongs, and Westworld is no exception to this. It’s like the entirety of HBO is a fourteen-year-old straight boy who’s just discovered the nascent thrill of drawing Sharpie-graffiti genitals on every available schoolyard surface and can only snigger, unrepentant and gleeful, whenever anyone asks them not to. We get it, guys – humans have tits and asses, and you’ve figured out how to show us that! Huzzah for you! Now get the fuck over your pubescent creative wankphase and please, for the love of god, figure out how to do it tastefully, or at least with some general nodding in the direction of an aesthetic other than Things I Desperately Wanted To See As A Teengaer In The Days Before Internet Porn.

That being said, I will concede that there’s an actual, meaningful reason for at least some of Westworld’s ubiquitous nudity: it’s a deliberate, visual act of dehumanisation, one intended not only to distinguish the hosts from the ‘real’ people around them, but to remind the park’s human employees that there’s no need to treat the AIs with kindness or respect. For this reason, it also lends a powerful emphasis to the moments when particular characters opt to dress or cover the hosts, thereby acknowledging their personhood, however minimally. This does not, however, excuse the sadly requisite orgy scenes, nor does it justify the frankly obscene decision to have a white female character make a leering comment about the size of a black host’s penis, and especially not when said female character has already been established as queer. (Yes, bi/pan people exist; as I have good reason to know, being one of them. But there are about nine zillion ways the writers could’ve chosen to show Elsie’s sexual appreciation for men that didn’t tap into one of the single grossest sexual tropes on the books, let alone in a context which, given the host’s blank servility and Elsie’s status as an engineer, is unpleasantly evocative of master/slave dynamics.)

And on the topic of Elsie, let’s talk about queerness in Westworld, shall we? Because let’s be real: the bar for positive queer representation on TV is so fucking low right now, it’s basically at speedbump height, and yet myriad grown-ass adults are evidently hellbent on bellyflopping onto it with all the grace and nuance of a drunk walrus. Elsie is a queer white woman whose queerness is shown to us by her decision to kiss one of the female hosts, Clementine, who’s currently deployed as a prostitute, in a context where Clementine is reduced to a literal object, stripped of all consciousness and agency. Episode 6 ends on the cliffhanger of Elsie’s probable demise, and as soon as I saw that setup, I felt as if that single, non-consensual kiss – never referenced or expanded on otherwise – had been meant as Chekov’s gaykilling gun: this woman is queer, and thus is her death predicted. (Of course she fucking dies. Of course she does. I looked it up before I watched the next episode, but I might as well have Googled whether the sun sets in the west.)

It doesn’t help that the only other queer femininity we’re shown is either pornography as wallpaper or female host prostitutes hitting on female customers; and it especially doesn’t help that, as much as HBO loves its gratuitous orgy scenes, you’ll only ever see two naked women casually getting it on in the background, never two naked men. Nor does it escape notice that the lab tech with a penchant for fucking the hosts in sleep mode is apparently a queer man, a fact which is presented as a sort of narrative reveal. The first time he’s caught in the act, we only see the host’s legs, prone and still, under his body, but later there’s a whole sequence where he takes one of the male hosts, Hector – who is, not coincidentally, a MOC, singled out for sexual misuse by at least one other character – and prepares to rape him. (It’s not actually clear in context whether the tech is planning on fucking or being fucked by Hector – not that it’s any less a violation either way, of course; I’m noting it rather because the scene itself smacks of being constructed by people without any real idea of how penetrative sex between two men works. Like, ignoring the fact that they’re in a literal glass-walled room with the tech’s eyerolling colleague right next door, Hector is sitting upright on a chair, but is also flaccid and non-responsive by virtue of being in sleep mode. So even though we get a grimly lascivious close-up of the tech squirting lube on his hand, dropping his pants and, presumably, slicking himself up, it’s not actually clear what he’s hoping to achieve prior to the merciful moment when Hector wakes up and fights him the fuck off.)

Topping off this mess is Logan, a caustic, black-hat-playing customer who, in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it foursome with three host prostitutes – two female, one male – is visually implied to be queer, and who thereinafter functions, completely unnecessarily, as a depraved bisexual stereotype. And I do mean blink-and-you’ll-miss-it: I had to rewind the episode to make sure I wasn’t imagining things, but it’s definitely there, and as with Elsie kissing Clementine, it’s never referenced again. The male host is engaging only with Logan, stroking his chest as he kisses and fucks the two women; it’s about as unsexualised as sexual contact between two naked men can actually get, and yet HBO has gone to the trouble of including it, I suspect for the sole purpose of turning a bland, unoriginal character into an even grosser stereotype than he would otherwise have been while acting under the misapprehension that it would give him depth. Spoiler alert: it didn’t. Logan doesn’t cease to be a cocky, punchable asshat just because you consented to put a naked white dude next to him for less time than it takes to have a really good shit; it just suggests that you, too, are a cocky, punchable asshat who should shit more in the bathroom and less on the fucking page. But I digress.

And then there’s the racism, which – and there’s no other way to put this – is presented as being an actual, intentional feature of the Westworld experience, even though it makes zero commercial sense to do this. Like. You have multiple white hosts who are programmed to make racist remarks about particular POC hosts, despite the fact that there are demonstrably POC customers paying to visit the park. You have a consistent motif of Native Americans being referred to as ‘savages’, both within Westworld-as-game and by the gamewriters themselves, with Native American mysticism being used to explain both the accidental glimpses various self-aware hosts get of the gamerunners and the in-game lore surrounding the maze. Demonstrably, the writers of Westworld are aware of this – why else is Episode 2, wherein writer character Lee Sizemore gleefully proposes a hella racist new story for the park, called ‘Chestnut’, as in old? I’ve said elsewhere that depiction is not endorsement, but it is perpetuation, and in a context where the point of Westworld as a commercial venture is demonstrably to appeal to customers of all genders, sexual orientations and races – all of whom we see in attendance – building in particular period-appropriate bigotries is utterly nonsensical.

More than this, as the openness with which the female prostitutes seduce female customers makes clear, it’s narratively inconsistent: clearly, not every bias of the era is being rigidly upheld. And yet it also makes perfect sense if you think of both Westworld and Westworld as being, predominantly, a product both created by and intended for a straight white male imagination. In text, Westworld’s stories are written by Lee and Robert, both of whom are straight white men, while Westworld itself was originally the conceit of Michael Crichton. Which isn’t to diminish the creative input of the many other people who’ve worked on the show – technically, it’s a masterclass in acting, direction, composition, music, lighting, special effects and editing, and those people deserve their props. It’s just that, in terms of narrative structure, by what I suspect is an accidental marriage of misguided purpose and unexamined habit, Westworld the series, like Westworld the park, functions primarily for a straight white male audience – and while I don’t doubt that there was some intent to critically highlight the failings of that perspective, as per the clear and very satisfying satirising of Lee Sizemore, as with Zack Snyder’s Suckerpunch and Lev Grossman’s The Magicians, the straight white male gaze is still so embedded as a lazy default that Westworld ends up amplifying its biases more often than it critiques them. (To quote something my straight white husband said while watching, “It’s my gaze, and I feel like I’m being parodied by it.”)

Though we do, as mentioned, see various women and people of colour enjoying the Westworld park, the customers who actually serve as protagonists – Logan, William and the Man in Black – are all white men. Logan is queer by virtue of a single man’s hand on his chest, but other than enforcing a pernicious stereotype about bisexual appetites and behaviours, it doesn’t do a damn thing to alter his characterisation. The end of season reveal that William is the Man in Black – that William’s scenes have all taken place thirty years in the past, shown to us now through Dolores’s memories – is a cleverly executed twist, and yet the chronicle of William’s transformation from youthful, romantic idealist to violent, sadistic predator only highlights the fundamental problem, which is that the Westworld park, despite being touted as an adventure for everyone – despite Robert using his customers as a basis for making universal judgements about human nature – is clearly a more comfortable environment for some than others. Certainly, if I was able to afford the $40,000 a day we’re told it costs to attend, I’d be disinclined to spend so much for the privilege of watching male robots, whatever their courtesy to me, routinely talk about raping women, to say nothing of being forced to witness the callousness of other customers to the various hosts.

It should be obvious that there’s no such thing as a universal fantasy, and yet much of Westworld’s psychological theorising about human nature and morality hinges on our accepting that the desire to play cowboy in a transfigured version of the old West is exactly this. That the final episode provides tantalising evidence that at least one other park with a different historical theme exists elsewhere in the complex doesn’t change the fact that S1 has sold us, via the various monologues of Logan and Lee, Robert and William and the Man in Black, the idea that Westworld specifically reveals deep truths about human nature.

Which brings us to Dolores, a female host whose primary narrative loop centres on her being a sweet, optimistic rancher’s daughter who, with every game reset, can be either raped or rescued from rape by the customers. That Dolores is our primary female character – that her narrative trajectory centres on her burgeoning sentience, her awareness of the repeat violations she’s suffered, and her refusal to remain a damsel – does not change the fact that making her thus victimised was a choice at both the internal (Westworld) and external (Westworld) levels. I say again unto HBO, I do not fucking care how edgy you think threats of sexual violence and the repeat objectification of women are: they’re not original, they’re not compelling, and in this particular instance, what you’ve actually succeeded in doing is undermining your core premise so spectacularly that I do not understand how anyone acting in good sense or conscience could let it happen.

Because in making host women like Dolores (white) and Maeve (a WOC), both of whom are repeatedly subject to sexual and physical violation, your lynchpin characters for the development of true human sentience from AIs – in making their memories of those violations the thing that spurs their development – you’re not actually asking the audience to consider what it means to be human. You’re asking them to consider the prospect that victims of rape and assault aren’t actually human in the first place, and then to think about how being repeatedly raped and assaulted might help them to gain humanity. And you’re not even being subtle about it, either, because by the end of S1, the entire Calvinistic premise is laid clear: that Robert and Arnold, the park’s founders, believed that tragedy and suffering was the cornerstone of sentience, and that the only way for hosts to surpass their programming is through misery. Which implies, by logical corollary, that Robert is doing the hosts a service by allowing others to hurt them or by hurting them himself – that they are only able to protest his mistreatment because the very fact of it gave them sentience.

Let that sink in for a moment, because it’s pretty fucking awful. The moral dilemma of Westworld, inasmuch as it exists, centres on the question of knowing culpability, and therefore asks a certain cognitive dissonance of the audience: on the one hand, the engineers and customers believe that the hosts aren’t real people, such that hurting them is no more an immoral act than playing Dark Side in a Star Wars RPG is; on the other hand, from an audience perspective, the hosts are demonstrably real people, or at the very least potential people, and we are quite reasonably distressed to see them hurt. Thus: if the humans in setting can’t reasonably be expected to know that the hosts are people, then we the audience are meant to feel conflicted about judging them for their acts of abuse and dehumanisation while still rooting for the hosts.

Ignore, for a moment, the additional grossness of the fact that both Dolores and Maeve are prompted to develop sentience, and are then subsequently guided in its emergence, by men, as though they are Eves being made from Adam’s rib. Ignore, too, the fact that it’s Dolores’s host father who, overwhelmed by the realisation of what is routinely done to his daughter, passes that fledgling sentience to Dolores, a white woman, who in turn passes it to Maeve, a woman of colour, without which those other male characters – William, Felix, Robert – would have no Galateas to their respective Pygmalions. Ignore all this, and consider the basic fucking question of personhood: of what it means to engage with AIs you know can pass a Turing test, who feel pain and bleed and die and exhibit every human symptom of pain and terror and revulsion as the need arises, who can improvise speech and memory, but who can by design give little or no consent to whatever it is you do to them. Harming such a person is not the same as engaging with a video game; we already know it’s not for any number of reasons, which means we can reasonably expect the characters in the show to know so, too. But even if you want to dispute that point – and I’m frankly not interested in engaging with someone who does – it doesn’t change the fact that Westworld is trying to invest us in a moral false equivalence.

The problem with telling stories about robots developing sentience is that both the robots and their masters are rendered at an identical, fictional distance to the (real, human) viewer. By definition, an audience doesn’t have to believe that a character is literally real in order to care about them; we simply have to accept their humanisation within the narrative. That being so, asking viewers to accept the dehumanisation of one fictional, sentient group while accepting the humanisation of another only works if you’re playing to prejudices we already have in the real world – such as racism or sexism, for instance – and as such, it’s not a coincidence that the AIs we see violated over and over are, almost exclusively, women and POC, while those protagonists who abuse them are, almost exclusively, white men. Meaning, in essence, that any initial acceptance of the abuse of hosts that we’re meant to have – or, by the same token, any initial excusing of abusers – is predicated on an existing form of bigotry: collectively, we are as used to doubting the experiences and personhood of women and POC as we are used to assuming the best about straight white men, and Westworld fully exploits that fact to tell its story.

Which, as much as it infuriates me, also leaves me with a dilemma in interpreting the show. Because as much as I dislike seeing marginalised groups exploited and harmed, I can appreciate the importance of aligning a fictional axis of oppression (being a host) with an actual axis of oppression (being female and/or a POC). Too often, SFFnal narratives try to tackle that sort of Othering without casting any actual Others, co-opting the trappings of dehumanisation to enhance our sympathy for a (mostly white, mostly straight) cast. And certainly, by the season finale, the deliberateness of this decision is made powerfully clear: joined by hosts Hector and Armistice and aided by Felix, a lab tech, Maeve makes her escape from Westworld, presenting us with the glorious image of three POC and one white woman battling their way free of oppressive control. And yet the reveal of Robert’s ultimate plans – the inference that Maeve’s rebellion wasn’t her own choice after all, but merely his programming of her; the revelation that Bernard is both a host and a recreation of Arnold, Robert’s old partner; the merging of Dolores’s arc with Wyatt’s – simultaneously serves to strip these characters of any true agency. Everything they’ve done has been at Robert’s whim; everything they’ve suffered has been because he wanted it so. As per the ubiquitous motif of the player piano, even when playing unexpected tunes, the hosts remain Robert’s instruments: even with his death, the songs they sing are his.

Westworld, then, is a study in contradictions, and yet is no contradiction at all. Though providing a stunning showcase for the acting talents of Thandie Newton, Evan Rachel Wood and Jeffrey Wright in particular, their characters are nonetheless all controlled by Anthony Hopkins’s genial-creepy Robert, and that doesn’t really change throughout the season. Though the tropes of old West narratives are plainly up for discussion, any wider discussion of stereotyping is as likely to have a lampshade hung on it as to be absent altogether, and that’s definitely a problem. Not being familiar with the Michael Crichton film and TV show, I can’t pass judgement on the extent to which this new adaptation draws from or surpasses the source material. I can, however, observe that the original film dates to the 1970s, which possibly goes some way to explaining the uncritical straight white male gazieness embedded in the premise. Even so, there’s something strikingly reminiscent of Joss Whedon to this permutation of Westworld, and I don’t mean that as a compliment. The combination of a technologically updated old West, intended to stand as both a literal and metaphoric frontier, the genre-aware meta-narrative that nonetheless perpetuates more stereotypes than it subverts, and the supposed moral dilemma of abusing those who can’t consent feels at times like a mashup of Firefly, Cabin in the Woods and Dollhouse that has staunchly failed to improve on Whedon’s many intersectional failings.

And yet, I suspect, I’ll still be poking my nose into Season 2, if only to see how Thandie Newton is doing. It feels like an absurdly low bar to say that, compared to most of HBO’s popular content, Westworld is more tell than show in portraying sexual violence, preferring to focus on the emotional lead-in and aftermath rather than the act itself, and yet that small consideration does ratchet the proverbial dial down a smidge when watching it – enough so that I’m prepared to say it’s vastly less offensive in that respect than, say, Game of Thrones. But it’s still there, still a fundamental part of the plot, and that’s going to be a not unreasonable dealbreaker for a lot of people; as is the fact that the only queer female character dies. Westworld certainly makes compelling television, but unlike the human protagonists, I wouldn’t want to live there.

from shattersnipe: malcontent & rainbows http://ift.tt/2jqQuUS via IFTTT

2 notes

·

View notes